Historical Background: The Kurdish Quest for Statehood

Downtown Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, which operates as a de facto state with its own government and international ties

The Kurds are often described as the world’s largest ethnic group without a state. Numbering over 30 million people across Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran, they have sought self-determination for over a century.

After World War I, colonial-era treaties (like the unfulfilled Treaty of Sèvres in 1920) dangled the idea of a Kurdish state, only for it to be quashed by the modern borders of the Middle East.

In the decades since, Kurds established autonomous regions where possible – notably the Kurdistan Region of Iraq – and waged insurgencies elsewhere.

A short-lived Republic of Mahabad in 1946 (in today’s Iran) proved fleeting, underscoring the Kurds’ uphill battle in gaining sovereignty.

In Iraq, Kurds secured autonomy after the 1991 Gulf War, eventually formalizing the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG).

The KRG has functioned like a state within a state since 1992, with its own parliament, military (Peshmerga), and even foreign relations.

By 2017, Kurdish leaders in Iraq felt confident enough to hold an independence referendum, where 92% voted in favor of full independence.

However, the Iraqi central government and neighboring states reacted harshly – Baghdad imposed sanctions and sent troops to assert federal control, while Turkey and Iran closed borders and threatened economically.

Western democracies offered little support, effectively sidelining the Kurdish bid for statehood despite its peaceful, democratic expression.

In Syria, the chaos of civil war allowed Syrian Kurds to carve out a self-governed zone called the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES), commonly known as Rojava.

Since 2012, Kurdish-led forces (the Syrian Democratic Forces, or SDF) have controlled this region, implementing a unique experiment in multi-ethnic, gender-equal governance.

Their fighters gained international acclaim as the most effective ground force against ISIS.

Yet despite this contribution, Syria’s Kurds have received no international recognition – on the contrary, Turkey invaded parts of Kurdish-held Syria, and even Western allies have largely stayed silent on Kurdish political rights.

The U.S.-led coalition maintains a military presence alongside the SDF to prevent an ISIS resurgence, implicitly helping the Kurds hold their territory, but the U.S. has not formally recognized even a measure of autonomy for Rojava.

In Turkey and Iran, where roughly half of all Kurds live, any move toward Kurdish independence is viewed as an existential threat.

Turkey fought a 40-year counterinsurgency against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) – an armed group seeking Kurdish autonomy – at the cost of tens of thousands of lives.

Iran has similarly suppressed Kurdish dissent, fearing separatism. Both states have historically cracked down on Kurdish language rights and political organizations to preempt any secessionist momentum.

This historical context sets the stage for today’s question: In light of recent developments, could an independent Kurdish state finally achieve recognition in the coming year? Below we examine the evolving geopolitics, the stances of key regional players (Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran), and the role of international powers – alongside an intriguing layer of insight from Orthodox Christian prophecies that foresee an independent Kurdistan as part of a larger divine plan.

Recent Geopolitical Developments Shaping Kurdish Aspirations

Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters stand on a military vehicle during operations against ISIS in eastern Syria. The yellow flag bears the emblem of the SDF, a Kurdish-led coalition instrumental in defeating ISIS and securing autonomous control in northeastern Syria.

Several major developments in the past few years have reshuffled the deck for Kurdish statehood aspirations:

Aftermath of the ISIS War: The defeat of ISIS by 2019, thanks in large part to Kurdish forces in Iraq and Syria, left the Kurds in control of larger territories than before. In Iraq, the KRG gained confidence (leading to the 2017 referendum), while in Syria the SDF solidified its hold over roughly one-quarter of the country. The Kurds’ sacrifices won them global admiration, but not sovereignty. Western powers praised Kurdish fighters for vanquishing ISIS yet still treated Kurdish independence as a “political inconvenience,” in stark contrast to their vocal support for other stateless nations like the Palestinians

2017 Independence Referendum Backlash: The KRG’s referendum, though landslide in result, triggered a swift rollback of Kurdish autonomy. Iraqi forces, with Iranian support, seized disputed territories (including oil-rich Kirkuk) from Kurdish control. Turkey closed airspace to the KRG. The message was clear: neighbors would not tolerate a unilateral Kurdish state, and the international community would not intervene on the Kurds’ behalf. This setback dampened open pushes for independence in the short term, but the desire for statehood remained deeply rooted among Kurds.

Turkey’s Shifting Stance (and War Fatigue): Under President Erdoğan, Turkey had moved from a hopeful peace process with Kurds (2013–2015) back to a hardline approach after the collapse of talks. However, an unexpected turn of events came in 2025: Abdullah Öcalan, the jailed PKK leader, issued an historic call ending the armed struggle. In a video message from prison, Öcalan announced “the end of the group’s armed struggle against Turkey,” urging the PKK to disarm and pursue democratic politics instead. By mid-2025 the PKK declared it was disbanding as an armed force after 40+ years of insurgency, holding symbolic disarmament ceremonies in Iraqi Kurdistan. Turkish officials, including President Erdoğan, cautiously welcomed this “voluntary transition” to peace – Erdoğan stated that “the winners of this process will be the whole of Turkey – Turks, Kurds and Arabs,” emphasizing hope for a new era without blood. If sustained, this Turkish-Kurdish détente could alter Ankara’s calculus: with the PKK threat neutralized, Turkey might feel less existentially threatened by Kurdish political gains. That said, Turkish leaders remain firmly against any independent Kurdish state on their borders, even if domestic conflict abates.

Syria’s Ongoing Uncertainty: Syria’s civil war is far from resolved, but as of late 2025 the Kurds still administer the northeast autonomously, while the Assad government and various rebel factions (and Turkish proxies) control other parts. The Kurds in Syria seek either autonomy or some form of federalism; outright independence is constrained by major powers. Russia (backing Assad) and Turkey (hostile to Rojava) both oppose Kurdish independence in Syria. The U.S. has tried to shield Rojava from Turkish invasion, especially in the final year of the Biden administration, reinforcing U.S. positions there to help Kurds hold their ground . Still, any lasting settlement for Syria will have to address the Kurds’ status – and there is a possibility that a new Syrian political order could legitimize Kurdish self-rule, if not full independence. Notably, the SDF’s success and governance have won begrudging respect; even France has acknowledged that “the Kurds of Syria shall have their role to play” in the country’s future.

Regional Realignments: The Middle East’s geopolitical landscape is shifting in ways that could either help or hinder Kurdish hopes. Arab states are reconciling with the Assad regime; Iran is under internal pressures; Turkey’s economy is struggling and it faces challenging regional diplomacy. There is speculation that great-power competition (U.S. vs Russia/Iran) could lead to Kurds being used as strategic pawns – for instance, Washington might find an independent Kurdistan useful to counter Iranian influence in Iraq, or to reward the Kurds for helping defeat ISIS. Conversely, if Turkey firmly aligns with the West (or if a post-Erdoğan government softens), Western powers might double-down on supporting Turkey’s unity to keep it happy, at the Kurds’ expense. The coming year will likely see continued negotiations and power-broking around these issues, such as talks about reintegrating Syrian Kurdish regions into a new Syrian political framework, and implementing the peace process in Turkey.

Regional Dynamics: Stakeholders in a Kurdish State

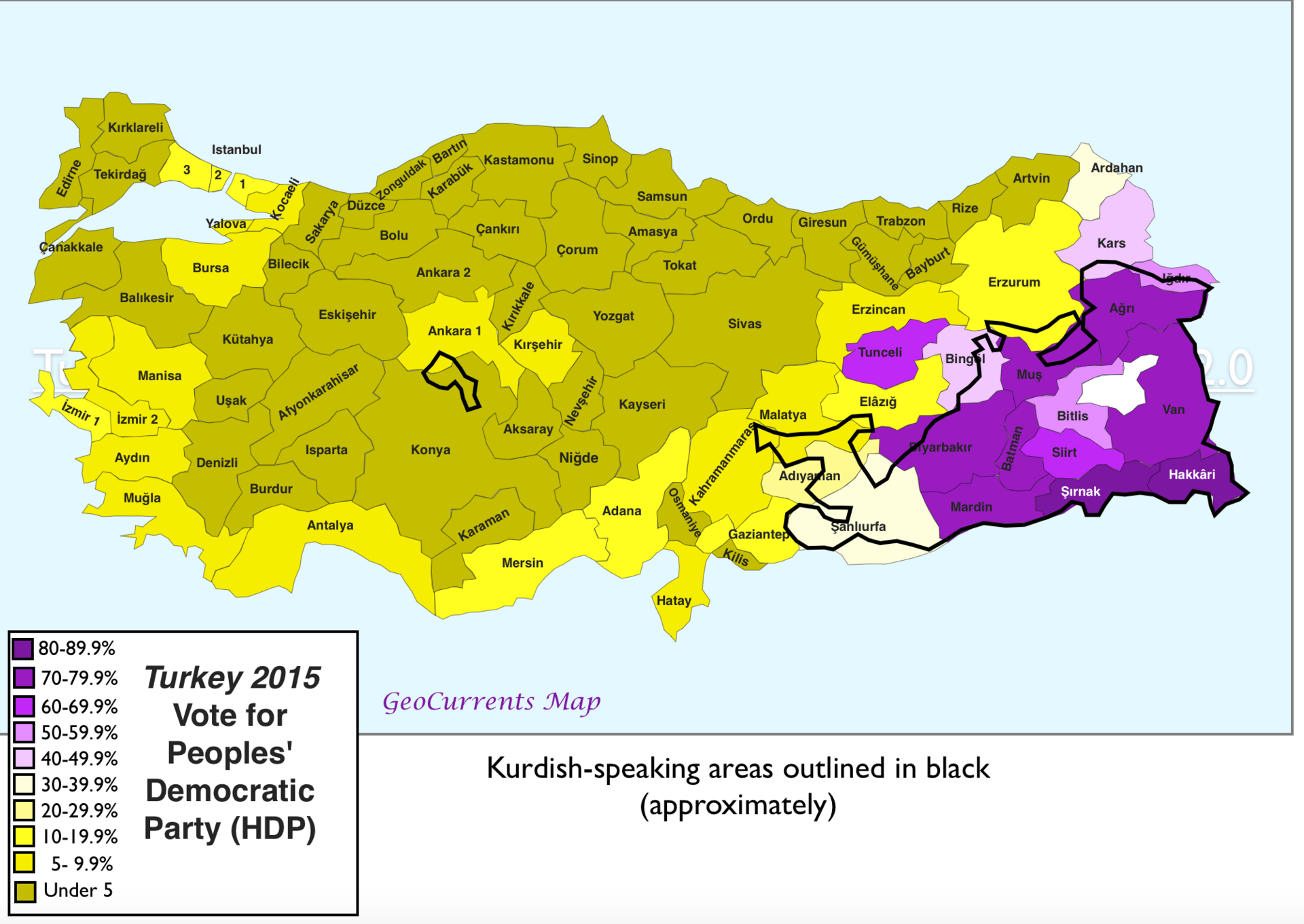

Map of Turkey showing 2015 voting percentages for the pro-Kurdish Peoples' Democratic Party (HDP)

Turkey’s Perspective

Turkey has the most to lose from an independent Kurdish state and has long been the fiercest opponent. About 15–20% of Turkey’s own population is Kurdish, mostly in the southeast. Ankara fears that an independent Kurdistan in Iraq or Syria would incite its own Kurds to seek secession. For decades Turkey pursued a hard assimilation policy internally, and it fought the PKK insurgency relentlessly (labeling the group as “terrorists,” with U.S./EU concurrence). Turkish leaders of all stripes (secular and Islamist alike) have viewed Kurdish independence as a red line for Turkey’s national security and territorial integrity.

However, Turkey’s stance is not entirely monolithic. Economically, Turkey developed a close partnership with the KRG in Iraq – Turkish businesses invest heavily in Iraqi Kurdistan, and until 2023 Turkey was the transit route for KRG’s oil exports. This pragmatic relationship led some to hope Turkey might tolerate an Iraqi Kurdish state under Masoud Barzani’s leadership, as long as Turkey’s own Kurds remained under control. Indeed, Turkey did not outright invade or attack the KRG during the 2017 independence bid, but it threatened punitive action and firmly backed Baghdad instead. Going into 2026, Turkey’s position seems to be softening in tone (with the peace process), yet it continues to insist on Syria’s territorial unity and cracks down on any hint of separatism at home. In short, unless a dramatic crisis or war intervenes, Turkey is unlikely to recognize a Kurdish state in the next year – in fact, it will pressure others to also withhold recognition.

Iraq’s Perspective

The federal government of Iraq has a constitutional framework that grants significant autonomy to the KRG, but Baghdad staunchly opposes independence. From Iraq’s view, Kurdish secession would mean losing a sizable chunk of territory, including oil fields, and could embolden other separatist movements. After the 2017 referendum, Baghdad not only militarily re-asserted control over disputed areas but also temporarily suspended Kurdistan’s oil exports and budget payments, forcing the KRG to back down. That said, relations have since been on a path of negotiation: Erbil (the KRG capital) and Baghdad periodically hash out revenue-sharing, oil laws, and security cooperation. As of late 2025, an interim deal reopened the crucial Iraq–Turkey oil pipeline, restoring some economic normalcy to Iraqi Kurdistan. Baghdad’s ideal scenario is to keep the Kurds within a unified Iraq, albeit with autonomy. The only foreseeable scenario where Iraq (reluctantly) lets Kurdistan go is if Iraq itself falls into chaos or if an international consensus forces Baghdad’s hand. Neither appears imminent in the next year. Thus, Iraq will continue offering the Kurds autonomy without sovereignty, at least for now.

Syria’s Perspective

The Damascus government under Bashar al-Assad has promised to eventually reintegrate the Kurdish regions, insisting on Syria’s unity. However, after years of civil war, Damascus lacks the capacity to retake the Kurdish-held northeast by force (especially with U.S. troops still present there). There have been on-and-off negotiations between Assad’s regime and the Kurdish autonomous administration; proposals generally revolve around cultural rights and local self-administration for Kurds in a future decentralized Syria, but not independence. Assad is backed by Russia and Iran – both oppose Kurdish independence (Russia fears a domino effect in its own Caucasus region; Iran fears it for reasons discussed below). One wildcard: if Syria’s regime were to change (e.g. a new government in Damascus more friendly to the West), it might conceivably strike a grand bargain with the Kurds. In early 2025 there were even reports of Syrian opposition forces ousting Assad (though unconfirmed), and suggestions that the U.S. and Russia might trade concessions involving the Kurds’ status. For the coming year, the likely outcome is a continued stalemate – the Syrian Kurds will govern themselves de facto, but neither Damascus nor any foreign state is poised to recognize a breakaway Kurdish republic.

Iran’s Perspective

Iran firmly rejects the idea of an independent Kurdistan. About 8-10% of Iran’s population is Kurdish, concentrated in the northwest (Iranian Kurdistan), and Iran has its own Kurdish dissident groups (like PJAK) which it suppresses. Tehran views any Kurdish state next door as an outpost of American and Israeli influence and a potential magnet for Iranian Kurds. In recent years, Iran has even launched missile strikes against Kurdish opposition bases in Iraq to show its determination to quash separatism. Moreover, a Kurdish state could threaten Iran’s strategic land routes (for instance, cutting the corridor to Syria/Lebanon if it emerged in northern Iraq). Iran cooperated with Turkey and Baghdad to isolate the KRG after the 2017 referendum, and it will undoubtedly do the same against any future Kurdish independence moves. The only scenario in which Iran might grudgingly accept a Kurdish state is one where Iran itself is internally weakened or undergoing political transformation – developments that are unpredictable in timing. As things stand, Iran will use its considerable influence in Baghdad and Damascus to block any recognition of Kurdish independence.

U.S. and International Involvement: Double Standards and New Calculations

Internationally, the Kurdish cause has long been met with sympathy in rhetoric but inaction in practice. No major power officially supports carving out a new Kurdish state, largely out of respect for the sovereignty of the states involved and fear of setting a precedent. However, the geopolitical winds are always shifting, and 2025 has highlighted some stark contrasts and evolving interests:

The Double Standard in Recognition: In late 2025, several Western countries moved toward recognizing Palestinian statehood – for example, France and Canada announced plans to recognize Palestine by September 2025, and the UK signaled it may follow suit. Kurds watched this with a mix of hope and frustration. On one hand, it shows international will to acknowledge stateless nations; on the other, “why not us?” Western governments have never even floated a U.N. resolution on Kurdish self-determination. As one commentator put it: “Why is Palestinian statehood deemed a matter of justice, while Kurdistan’s statehood is treated as a political inconvenience?'‘ The Kurds’ consistent alignment with the West (fighting ISIS, embracing democracy) has earned them applause but not sovereignty. This double standard is becoming more glaring, and Kurdish advocates are pressing the issue in international forums and media. It’s possible that continued Western recognition of Palestine might pave the way for greater discussion of Kurdish statehood as well – though no government has yet indicated such a plan.

United States Policy: The U.S. finds itself in a delicate balancing act. It has been the Kurds’ closest international partner militarily (especially in Syria and previously via the no-fly zone in Iraq). American special forces and diplomats work closely with Kurdish leaders. Yet the U.S. also values the unity of Iraq (to contain Iran) and relies on Turkey as a NATO ally. Official U.S. policy still supports Iraq’s territorial integrity and a unified Syria. In 2017, Washington actually opposed the KRG’s unilateral independence referendum and urged Kurdish leaders to settle for autonomy. At the same time, Washington has provided political cover and protection for the Syrian Kurdish administration by keeping troops on the ground – effectively ensuring a Kurdish zone survives in Syria. As the Biden administration ended its term, it took steps to fortify Rojava against potential threats, and U.S. officials laud the Kurds’ role in defeating ISIS. Still, U.S. support has limits: for instance, when Syrian Kurds attempted local elections that might “legitimize” their administration, U.S. officials discouraged it so as not to anger Turkey. In the coming year, much depends on U.S. strategic priorities: if countering Iran or Russia takes precedence, the U.S. might empower the Kurds more (even hinting at statehood as leverage); conversely, if stabilizing relations with Turkey is key (especially under a new U.S. administration), Kurdish aspirations might be placed on the back burner again.

Europe and Others: European countries have historically championed human rights for Kurds (pressuring Turkey to improve cultural rights as an EU accession condition, for example), but they too stop short of backing independence. Europe’s worry is that a Kurdish state could destabilize an already volatile region and trigger refugee flows or new conflicts. However, within Europe there are voices of change – several European Parliament members and national parliaments’ resolutions have urged support for Kurdish self-determination in the context of thanking the Kurds for fighting ISIS. Russia’s role is complex: at times Moscow has courted the Kurds (it once allowed a Syrian Kurdish mission in Moscow to open), using them as a card against Turkey; yet Russia ultimately sides with Damascus and Tehran in opposing a Western-aligned Kurdish state. Notably, Israel is one of the few countries that has quietly supported Kurdish independence – seeing Kurds as non-Arab, non-Islamist allies in the region. Israeli flags were even waved in Erbil during the 2017 referendum celebrations. But even Israel has not formally recognized Kurdistan, likely to avoid antagonizing Turkey and because open support could be used by Iran to discredit the Kurds.

In the international legal arena, Kurdish representatives often highlight that their case meets the same criteria used to justify other new states: a distinct people with a common language and culture, control of territory, proven ability to govern, and a historic grievance of persecution. Article 1 of the UN Covenant on Civil and Political Rights affirms the right of “all peoples” to self-determination. Despite this, realpolitik prevails – global recognition requires major power backing, which the Kurds lack so far.

One scenario that could change calculations is a major regional war or collapse of a current state, providing an opportunity (or pretext) for Kurdistan to emerge. Interestingly, this is precisely the scenario foreseen in certain Orthodox Christian prophecies, which we turn to next.

Orthodox Christian Prophecies of a Kurdish State: Saint Paisios’ Vision

Photograph of Saint Paisios the Athonite (1924–1994)

Beyond the secular analysis, the Kurdish question also appears in the spiritual and prophetic tradition of the Eastern Orthodox Church. In particular, Saint Paisios of Mount Athos (1924–1994) – a revered Greek Orthodox monk canonized for his wisdom and clairvoyant gifts – made striking prophecies about the future of Turkey and the emergence of a Kurdish state. His words, recorded by pilgrims and later published, have gained fame for seemingly predicting geopolitical shifts in the region.

Saint Paisios the Athonite (1924–1994) was renowned for bold prophecies about future wars and the fate of Turkey Saint Paisios’ Prophecy of Turkey’s Dissection: Paisios foretold a time when Turkey – a nation he saw as having arisen “without God’s blessing” – would be partitioned into multiple parts after a great war. Remarkably, he specified the beneficiaries of this partition:

«Η Τουρκία θα διαμελισθεί σε 3-4 κομμάτια… Εμείς θα πάρουμε τα δικά μας εδάφη, οι Αρμένιοι τα δικά τους και οι Κούρδοι τα δικά τους. Το κουρδικό θέμα έχει ήδη δρομολογηθεί… όταν θα πάψει αυτή γενιά που κυβερνάει την Τουρκία και θα αναλάβει νέα γενιά πολιτικών.»

“Turkey will be partitioned into 3 or 4 parts... We (Greeks) will take our lands, the Armenians theirs, and the Kurds their own. The Kurdish issue has already been set in motion. These things will happen – not immediately, but soon – when the current generation ruling Turkey passes and a new generation of politicians comes to power.”)

According to Saint Paisios, the “countdown” had already begun for this outcome. He often linked it to a war involving major powers: for example, he believed a conflict over the Aegean (“Eximilia” – six nautical miles) would draw in Russia, leading to Turkey’s downfall and the restoration of Constantinople to Greece. In the chaos, Kurds and Armenians would finally gain independence on their ancestral lands – essentially, an independent Kurdistan and a free Armenia would be carved out of eastern Turkey.

Saint Paisios’ prophecy explicitly mentions the Kurds’ struggle. He reassured listeners not to fear Turkish aggression because, in his view, Turkey’s dissolution was in God’s plan. On one occasion, he even pinpointed a geopolitical logic: after a Muslim state (Bosnia) was created in Europe in the 1990s, the West would turn and tell Turkey “now the Kurds and Armenians should also gain independence in the same way”. As he vividly put it:

«Βλέπω όμως να διαλύουν την Τουρκία με ευγενικό τρόπο: Θα ξεσηκωθούν οι Κούρδοι και οι Αρμένιοι και θα ζητήσουν οι Ευρωπαίοι να ανεξαρτητοποιηθούν και τα έθνη αυτά… Έτσι «ευγενικά» θα κομματιάσουν την Τουρκία.»

(“I see them dissolving Turkey in a ‘polite’ way: The Kurds and Armenians will rise up, and the Europeans will demand that these nations become independent... Thus, ‘politely,’ they will cut Turkey to pieces.”)

This startling prophecy suggests that European powers (and broadly, the “allies”) will one day support Kurdish independence as part of redrawing Turkey’s map – essentially flipping the script to favor those minorities, under the guise of fairness (having earlier enabled a Muslim-majority state in Europe, i.e., Bosnia). Paisios often emphasized that Allied forces would ultimately destroy Turkey, not Greece itself: “Turkey will be destroyed by its allies… it will be for our benefit”, he told visitors.

«Και πότε θα γίνουν αυτά; Όταν οι Η.Π.Α. ανακηρύξουν την ίδρυση ανεξάρτητου Κουρδικού κράτους μου τότε κοντά είναι», εκμυστηρεύτηκε ο Άγιος Παΐσιος σε ένα αγαπημένο του παιδί που βρίσκεται σήμερα εν ζωή.»

(“"And when will these things happen? When the U.S.A. declares the establishment of an independent Kurdish state, then it is near," Saint Paisios confided to a beloved spiritual child who is still alive today.”)

Moving into 2026, what to Expect

as we head into 2026, the potential recognition of an independent Kurdish state stands at the nexus of recent geopolitical shifts and long-held spiritual expectations. While immediate official recognition would require a bold leap by the international community (or a radical change in regional dynamics), the momentum of events is unmistakably moving in the Kurds’ favor compared to past decades. They now have autonomous zones, battle-tested armed forces, and a narrative of resistance against extremism that has earned global respect.

The U.S. and others remain involved on the ground, and talk of peace and rights is replacing talk of terror and insurgency. Whether change comes through incremental political deals or is thrust upon the world by conflict, the idea of “Kurdistan” is closer to reality than ever before. As Saint Paisios advised, one should keep faith and hope – for if his words ring true, “Όλα αυτά θα γίνουν… Έφτασε ο καιρός” (“All these things will happen... The time has come”) And even in realpolitik terms, one cannot rule out that in the not-so-distant future, the Kurds might finally take their rightful place on the map, turning prophecy into history.

📘 Geopolitical and Historical Sources

Al Jazeera. (2025, June 10). PKK announces end of armed struggle, calls for peace with Turkey. https://www.aljazeera.com

BBC News. (2017, October 16). Iraqi army seizes Kirkuk from Kurdish control. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41631673

Foreign Policy. (2023, March 3). How the West abandoned the Kurds—again. https://foreignpolicy.com

Middle East Forum. (2025, May 22). Why no one recognizes Kurdistan? https://www.meforum.org

Reuters. (2025, April 30). Iraq, KRG reach interim oil deal as pipeline reopens. https://www.reuters.com

The Guardian. (2022, August 4). US military still partnering with Kurdish forces in Syria. https://www.theguardian.com

U.S. Department of State. (2024). Country reports on human rights practices: Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Iran. https://www.state.gov/reports

United Nations. (1966). International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Treaty Series, vol. 999, p. 171. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/international-covenant-civil-and-political-rights

📖 Orthodox Christian Prophetic Sources

Paisios of Mount Athos. (1999). Spiritual counsels II: Spiritual awakening (Elder Paisios the Athonite). Holy Monastery of Evangelist John the Theologian. (Original work published in Greek: «Πνευματικές Ομιλίες, Τόμος Β’: Πνευματική Αφύπνιση»)

Αγιορείτικο Βήμα. (n.d.). Ανεκδοτες μαρτυρίες Αγίου Παϊσίου. Retrieved December 2025, from https://www.agioritikovima.gr

Cosmas of Aetolia. (2007). Prophecies of Saint Cosmas. Athens: Orthodox Kypseli Publications. (Original work published ca. 18th century)

Kitsikis, D. (2004). The Ottoman space: Civilization, ideology, geopolitics [in Greek]. Athens: Esoptron.

Pemptousia. (2023). Prophecies of Elder Paisios about Turkey and the Kurds. https://pemptousia.com

Orthodox Watch. (2024). The role of Orthodox prophecy in modern geopolitics. https://orthodoxwatch.org